by Helaina Gaspard

Introduction

Over the last two years, First Nations child welfare has attracted national attention as one, among several challenges in need of immediate action and reform. A critical juncture was the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal’s (CHRT) January 2016 ruling that found the federal government’s First Nations Child and Family Services program to be discriminatory to children on reserve because of inequitable funding levels for child welfare services. The CHRT demanded the federal government reform the system.

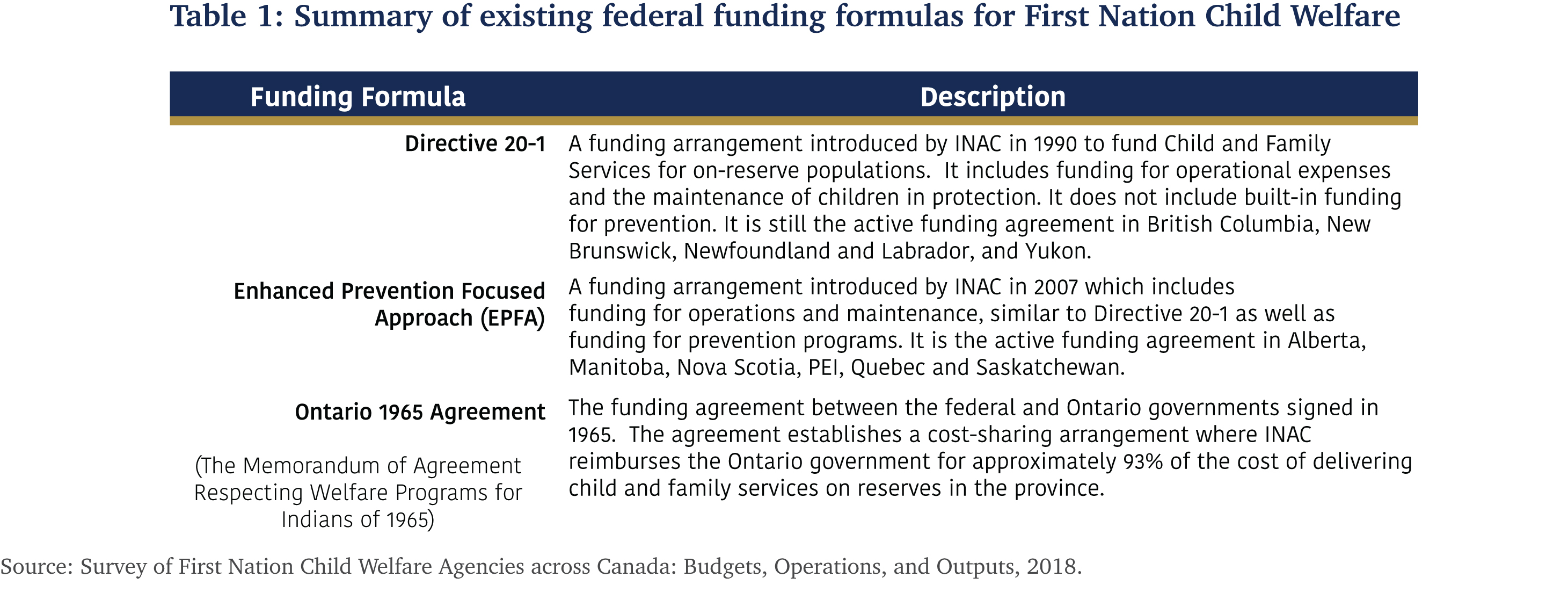

The federal government funds on-reserve child welfare through three funding agreements with the provinces[1] (see Table 1). Each of the formulas fund agencies’ operational expenses and the cost of children in the protection system, with some differences such as funding for prevention. All three formulas however, tend to require that children enter into care in order to unlock funding. In recognition of the institutional challenges, Ontario’s Ministry of Child and Youth Services requested the IFSD explore alternative funding formulas for improved outcomes for children in care.

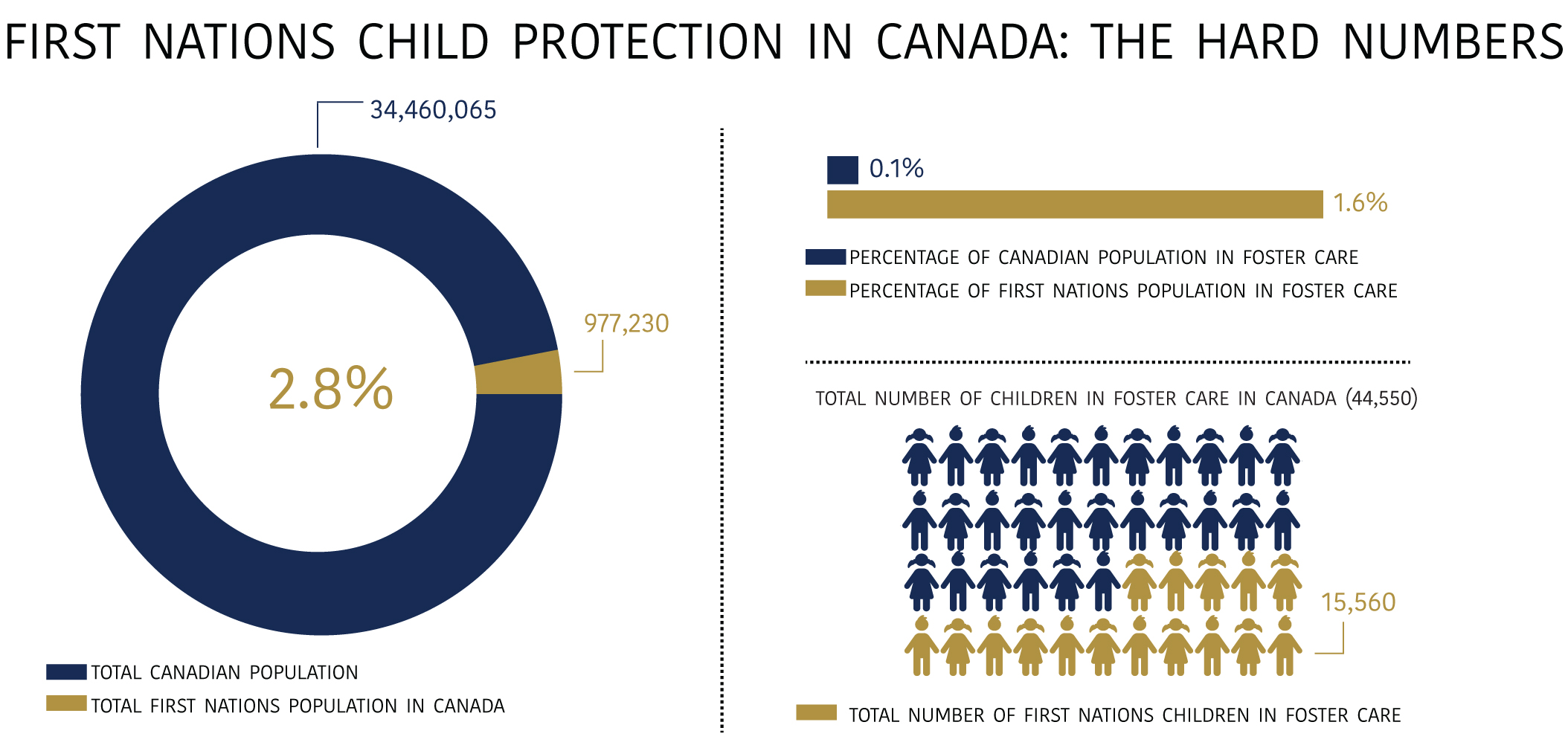

The rates of First Nation children in care are significant, relative to their proportion of the population (see Figure 1). According to 2016 Census data from Statistics Canada, First Nations people represent just under 3% of the total Canadian population, yet First Nations children makeup 35% of all children in foster care[2]. To put this in perspective, the population of 44,550 children in foster care in Canada is larger than the total population of many small Ontario towns like Chatham, St-Thomas, or Leamington.*

Details and data to support better decision-making in child welfare are sparse at the national level, especially when it comes to First Nations children. For instance, there has been no national study in nearly ten years on why children enter into care. The last Canadian Incidence Study (CIS)[3] that tracked this information was completed in 2008, leaving an important gap in understanding of current trends in child welfare. Knowing that there are a disproportionate number of First Nations children in care highlights the need for improved information to shape an informed response. Why the children are entering into care, where they go once they’re in care, what services they access, and what results they achieve are critical to understanding how Canada should orient and improve its child welfare system and its results for First Nations peoples.

First Nations Child Welfare Agencies

On the front lines of this issue are the First Nations child welfare agencies that are accountable for delivering protection and related services to on-reserve populations. There are 109 such agencies across Canada, and results of a first-of-its-kind survey undertaken by IFSD at the request of the National Advisory Committee (NAC) suggest that the agencies are as heterogeneous as the communities they serve.

Agency budgets are made up of a combination of federal and provincial funding determined by their current agreement (see Table 1). According to Indigenous Services Canada’s (ISC) (formerly, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC)) 2016-2017 Departmental Results Report, a total of $768,037,213 was spent on the First Nations Child and Family Services program (an increase of $87,142,057 over last year’s spending) that would have been allocated to fund agencies and their services[4]. These numbers don’t mean much without a comparison, but First Nation and non-First Nation agency comparisons can be challenging as there are significant gaps in data reified by well-guarded jurisdictional boundaries (i.e. agency; provincial; federal). Agency consultations suggest that budgets are often over-stretched, near deficit or in deficit, especially when it comes to funding prevention programs and services. A British Columbia First Nations agency has for instance, resorted to paying its staff $6 per hour less than their provincial counterparts in order to fund prevention programming[5].

The federal government has legal and fiduciary obligations under the Indian Act that it must uphold to Canada’s Indigenous Peoples. Whatever your political or moral suasions may be on this issue, there is no question that as a matter of publicly funded policy, there are more effective ways of protecting and of improving outcomes for First Nations children in care. The federal government is obliged to fund it, so why not do it effectively? There are agencies across the country who have been successful in navigating the multi-tiered funding structure and who have enhanced their program offerings, and in some instances, reduced the rates of children in care, and managed to promote family integration.

As the entities accountable for fulfilling their legislated child protection obligations and for providing a breadth of related services, agencies understand the operational, organizational, and financial realities of supporting and upholding the child welfare system. Policymakers stand to learn a great deal from agencies that could inform a new approach to funding.

Closing the funding gap in the current system that’s not working is not a solution by itself. More is required. A renewed system that drives better results for children and eliminates funding inequities should be the goal. Getting to a new approach will require collaboration and commitment from First Nation communities, agencies, and both federal and provincial governments. It is also important to identify existing wise practices that could serve to orient new approaches to First Nation child welfare. Initial consultations with agencies in three provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan) suggest that when it comes to areas of funding, protection, prevention, people (i.e. staff), and data matter to get to better results for children.

Protection

A central role for child welfare agencies is protection whether the agency is delegated (i.e. tasked with investigating claims of maltreatment and placing children in care) or non-delegated (i.e. overseeing the child’s well-being once the decision has been made that they enter care). Consistent with research findings from non-First Nations[6] communities, effective First Nations child welfare agencies tend to focus on wrap-around services that surround a family in crisis with the intent of keeping or returning children to their home communities (especially if they are in care).

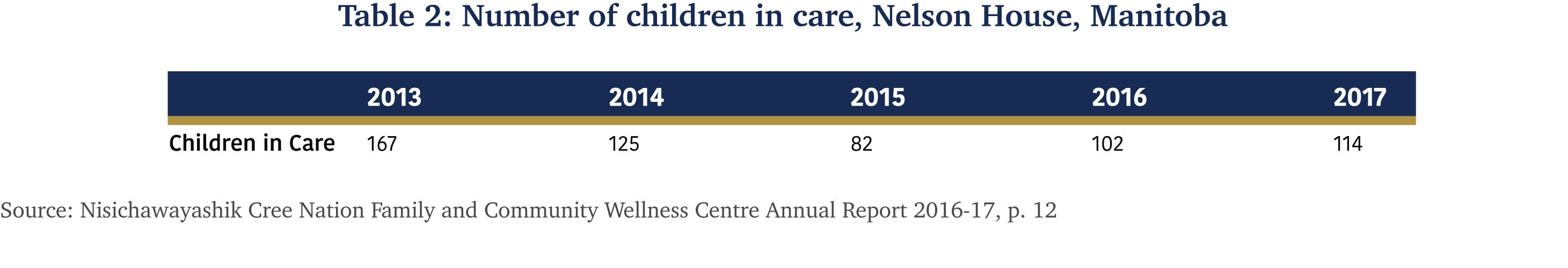

At the Nisichawayashik Cree Nation Family and Community Wellness Centre, Felix Walker, the Centre’s executive director has been innovating in child welfare services since his appointment in 2001. At the time, elders were concerned with the high child apprehension rates in their community. Walker was prompted to action when elders asked him why children were being removed from their homes when their parents were the problem. At the Nelson House (Manitoba) location, the Centre introduced the Intervention and Removal of Parents Program beginning in 2002. Novel at the time, the Centre worked to encourage a Band Council Resolution requiring the removal of anyone causing harm to children from a home on-reserve. As the landlord of all homes on-reserve, the Band Council could refuse tenancy to anyone harming children. The Centre could then keep children in need of protection in their homes with a member of their extended family or with an emergency worker. The approach flipped the traditional protection model on its head: instead of removing children from their home, parents were removed and were forced to face trauma as would their children being placed in foster care, not knowing where they were going or who would care for them. Since 2013, rates of children in care at the Nelson House location have declined from 167 to 114 in 2017[7] (see Table 2). According to the Centre, with the Removal of Parents Program and an integrated approach to family care, the agency has been able to reunify families 85% of the time[8].

Prevention

Preventive child welfare services are a continuum of services from public education campaigns for the general population, to targeted programs for at risk populations, to intensive family preservation programs to assist families in crisis. Preventive care can address the physical and mental health of the child, can teach good parenting practices, can address underlying causes of neglect such as poverty and can counsel and support a family in crisis. More than a clinical approach to care, prevention programs and initiatives are designed to heal, and to promote the development of life skills. Preventive care can keep children out of the protection system, can support their reunification with their family (in an improved environment) after protection, and can also support children who are not in the protection system. At its core, preventive care is about wrap-around services and support for a community in order to build social trust, that educates, and promotes health and wellness.

Critical to preventive services is an integrated approach to care. Kanaweyimik Child and Family Services in Saskatchewan encourages the approach by facilitating monthly inter-agency meetings with key service providers including those in health, social development, education, justice, members of the RCMP, as well as Kanaweyimik and band officials[9]. The objective of these meetings is to improve services to community members by creating effective partnerships and awareness of what services are offered by various service providers.

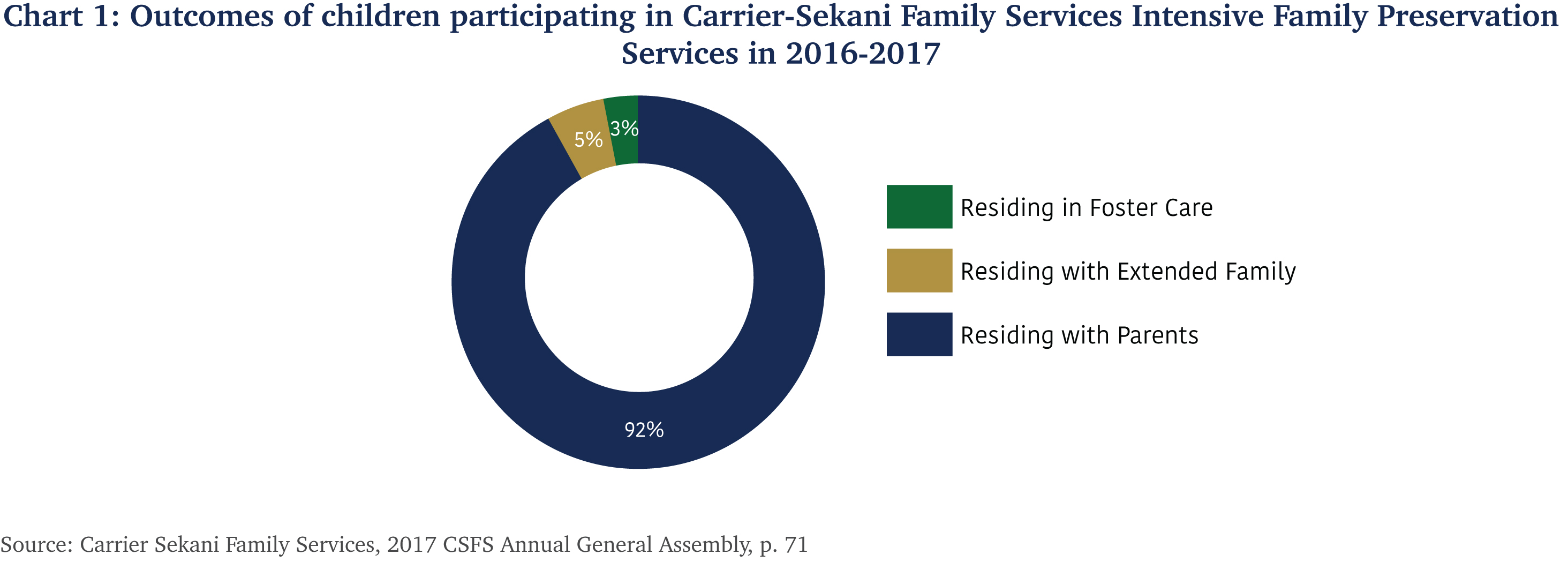

In British Columbia, Mary Teegee and her team at Carrier Sekani Family Services in Prince George have tracked outcomes for children in their Intensive Family Preservation Services in 2016-2017. This 28-day program includes in-home counselling and crisis intervention, the direct support of a clinician for 10 hours a week, as well as the ability to access support 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The outcomes for children participating in the program have been positive. Of 66 participating cases, 61 have resided with their parents, 3 resided with extended family, and only 2 resided in foster care (see Chart 1)[10].

Drawing a causal link between preventive care and a reduction in the number of child protection cases is difficult. Initial results from different agencies suggest however, that there is a correlation between prevention programming and a reduced number of cases. It remains unclear if kids from community-based care fare better than those in the provincial system over the long-term (not enough time has passed to make that assessment). What is clear according to the consulted agencies, is that in the short-term those who engage in community care have a sense of belonging, stability, and identity.

People

In a career that manages complex and emotional cases, a supportive work environment for staff is critical for their own mental health and the sustainability of the organization. Kanaweyimik Child and Family Services, integrates weekly meetings which include a ceremony with elders. At the circle meetings, the team can bring their challenges and issues (both personal and professional) so that their colleagues are aware and can help to support them. An agency’s program delivery and success depend on the competency of its staff, and directors are committed to fostering opportunities for professional development from annual conferences to special training.

At the Nisichawayashik Cree Nation Family and Community Wellness Centre, Walker invested in staff by buying a social work program at the University of Manitoba. In 2012-2013, 22 full-time staff enrolled and had their tuition fees covered (as long as they continued to work in good standing at the Centre). The program’s first cohort will graduate in 2019-2020. Continued skill development and training of agency staff can promote staff retention and community growth (as many staff are community members too). A new approach to First Nation child welfare should include an allocation for staff development. It would serve to both bolster agencies and support communities.

Data and evaluation

Across the three agencies mentioned above with wise practices to share is a common commitment to the use of their own data for decision making. The agencies collect and use data to evaluate their programs, to adjust them based on community needs, and to undertake strategic planning exercises for the medium- and long-term trajectories of their communities.

Monthly data collection at Nisichawayashik Cree Nation Family and Community Wellness Centre is used to understand if child and family uptake of services change with increased participation in health and prevention activities. Research by Kanaweyimik Child and Family Services found that poverty affects between 85%-90% of its community members at varying times. It used the findings to design a family engagement program that funds family time with activities as simple as bowling, a meal, and money for gas. The program is intended to encourage the family to spend quality time together even when they’re faced with challenges (the program is so popular, it has a wait-list).

Community connections and community trust underpin an agency’s ability to fulfill its mandate fulsomely. Regular data collection, community consultations, and performance reporting are already in practice in various agencies. A new arrangement for First Nation child welfare should leverage these experiences and include outcome-oriented performance reporting across funding areas (where applicable).

Conclusion

If the success of the agencies featured in these case studies can serve as evidence that replicable wise practices exist within First Nations communities, then the four factors of protection, prevention, staff development and data collection can be considered the drivers of positive outcomes for children in care and can serve as the foundation to orient discussions on new approaches and funding formulas.

[1] Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), “National Social Programs Manual,” June 19, 2012, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1335464419148/1335464467186#chp6 . See also IFSD, Survey of First Nation Child Welfare Agencies across Canada: Budgets, Operations, and Outputs, 2018.

[2] Statistics Canada, “Data Products, 2016 Census,” January 3, 2018, http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/index-eng.cfm .

* Statistics Canada and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) (formerly, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada), report different numbers of First Nations in children in care. ISC reported 8,483 children in care in 2015-2016 (see https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1100100035204/1100100035205), which differs from the 15,560 reported by Statistics Canada. For consistency in analysis, only Statistics Canada’s 2016 Census data is used here.

[3] Canada, 2008 Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect, 2010, http://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/en/CIS-2008-rprt-eng.pdf

[4] Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), “Departmental Results Report 2016-17,” November 9, 2017, https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1502130801458/1502132735866 .

[5] Interview by Author, 2017.

[6] See for instance, Manitoba, Families First Program Evaluation, 2010, https://www.gov.mb.ca/healthychild/familiesfirst/ff_eval2010.pdf ; Mark Chaffin et al., “A Statewide Trial of the SafeCare Home-based Services Model With Parents in Child Protective Services,” Pediatrics vol. 129, no. 3. 2012.

[7] Nisichawayashik Cree Nation Family and Community Wellness Centre, Annual Report 2016-17, 2017, http://www.ncnwellness.ca/wp-content/uploads/AnnualReport_2017_web.pdf

[8] Nisichawayashik Cree Nation Family and Community Wellness Centre, Interview by Author, 2017.

[9] Kanaweyimik Child and Family Services Inc., Interview by Author, 2017.

[10] Carrier Sekani Family Services, 2017 CSFS Annual General Assembly, 2017, http://www.csfs.org/uploads/CSFS%2027th%20Annual%20AGA%20Booklet%20WEB.pdf