by Dominique Lapointe

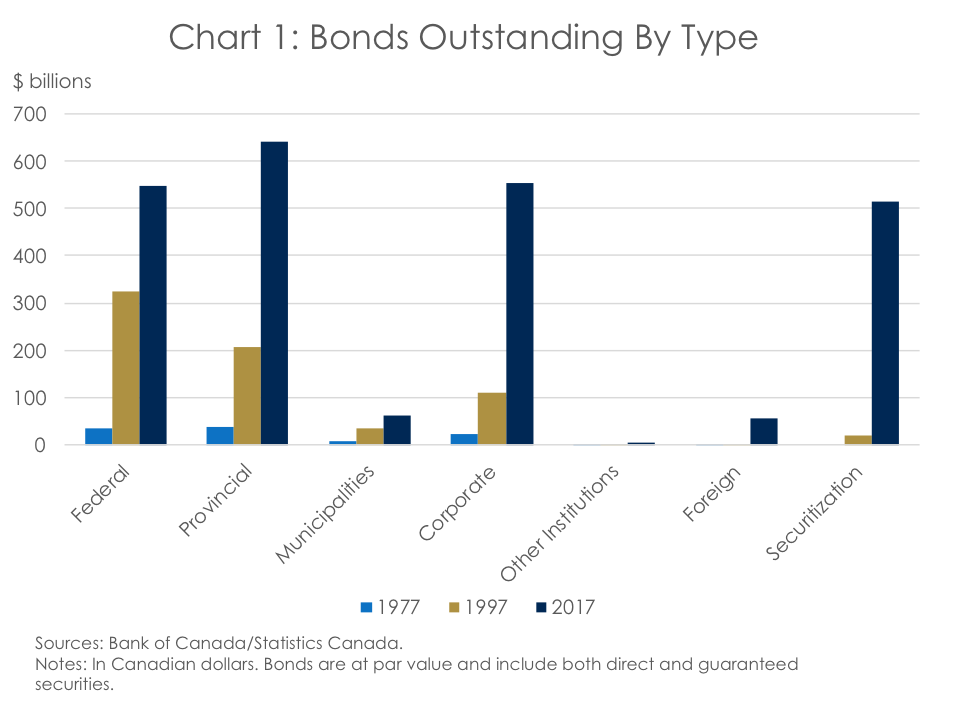

The market for Government of Canada securities is closely scrutinized by analysts, market participants, and government officials themselves. The market for provincial bonds generally receives less attention. However, at $642 billion in 2017 and representing 27% of capital markets in Canada, the market for provincial bonds was larger in size than that of the federal government at 23% (Chart 1). As some provinces will likely continue to finance important deficits by borrowing from financial markets and diversifying their borrowing methods, it is crucial to understand the dynamics at play in this segment of the market.

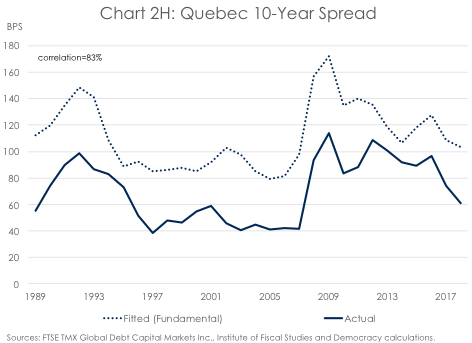

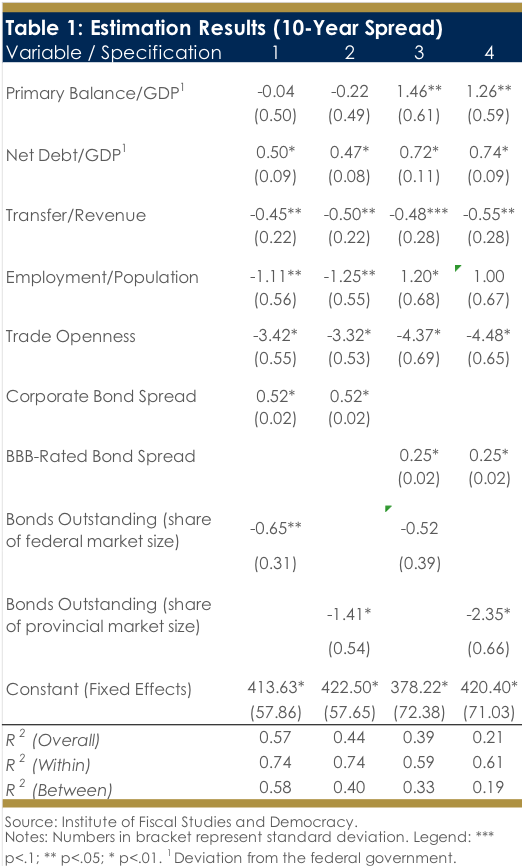

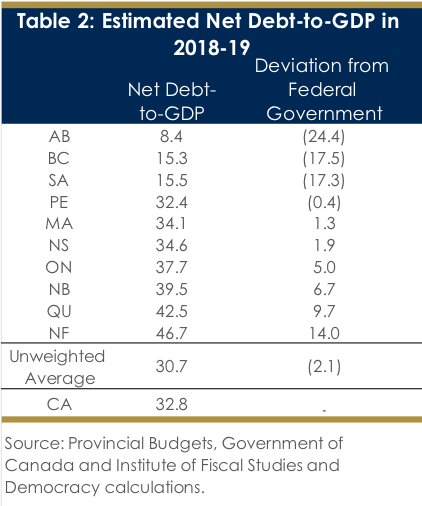

In its latest report, the Institute of Fiscal Studies and Democracy (IFSD) investigates if, and by how much, fiscal discipline matters for provincial-Canada yield differentials. To do so, we build on existing literature on subnational spreads and decompose annual provincial yield spreads by their fundamental drivers: fiscal stress, risk aversion, liquidity, transfer dependency, trade openness, and employment (Table 1). We find that fiscal soundness at the provincial level consistently compresses yield spreads both at the 10- and 5-year bond maturity. Specifically, a 1 percentage point decrease in a province’s net debt-to-GDP ratio decreases provincial-Canada fundamental spread by 0.5 and 0.05 basis points at the 10- and 5-year maturity, respectively. While this might seem small, considering current debt levels, this amounts to a 5 spread basis points premium for Quebec, and 7 for Newfoundland. This also is a 12, 9, and 9 spread basis point discount for Alberta, British Columbia, and Saskatchewan at the 10-year maturity, respectively (Table 2). Unlike previous studies, we do not find a significant impact of deficit-to-GDP on subnational spreads. While different data and methodology used can explain that discrepancy, it is also possible that, since deficits ultimately result in higher debt, both variables encapsulate fiscal stress the same way.

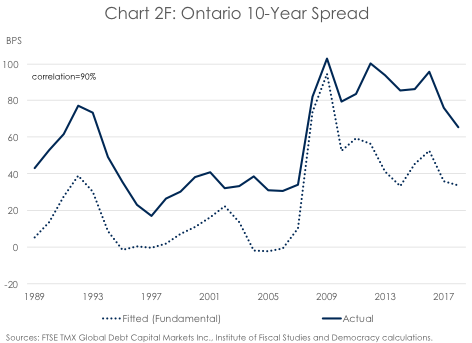

Additionally, assuming perfect liquidity in the federal bond market, a 1% increase in a province’s outstanding amount of bonds relative to that of the federal government decreases its fundamental 10-year spread by 0.7 basis points. Henceforth, bigger provinces such as Ontario and Quebec, with deeper and larger markets for their bonds, benefit from a liquidity discount. It is worth emphasizing that this proxy for liquidity remains indirect.

Global risk aversion as imbedded in corporate bond spreads remains a major factor influencing provincial-Canada bond spreads. A 1-basis-point increase in Investment Grade (IG) corporate spread increases provincial spreads by 0.5 basis points. This supports the hypothesis that provincial bonds are seen by investors as substitutes for IG corporate bonds. A related finding is that, over the long-term, provincial-Canada yield spreads exhibit more variation over time than between provinces, highlighting the importance of common factors such as risk aversion in explaining yield differentials. We also investigated whether the importance of federal transfers such as equalization payments, Canada Health Transfer, and Canada Social Transfer reduce provincial yields by providing an implicit bailout policy. We find that higher transfers-to-revenues tend to compress long-term yields, which we see as a form of risk-sharing across the country. Finally, trade openness and employment-to-population ratio, proxies for a province’s capacity to attract capital and collect taxes, respectively, dampen yield spreads.

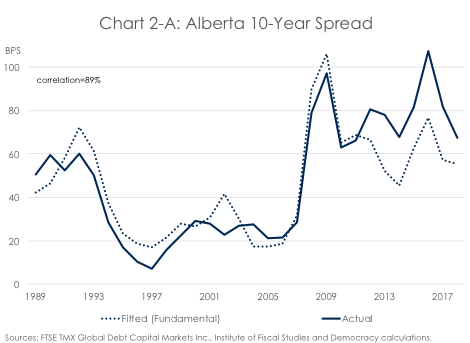

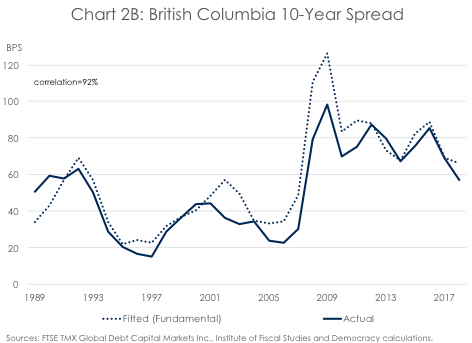

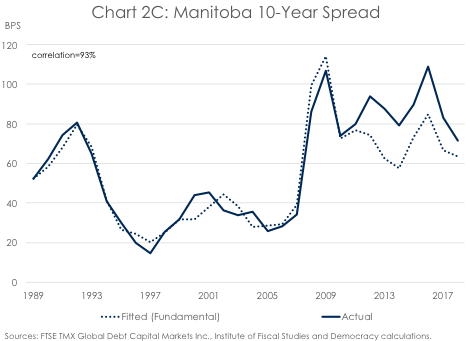

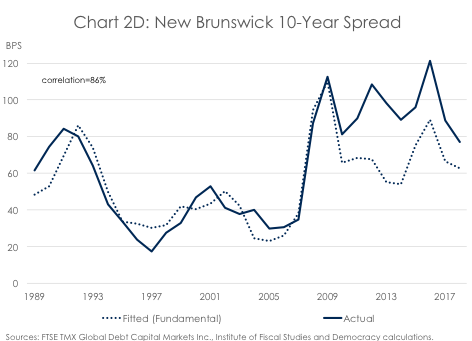

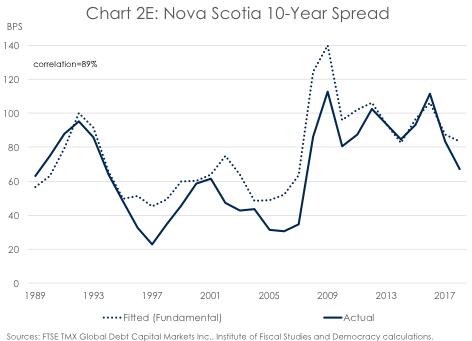

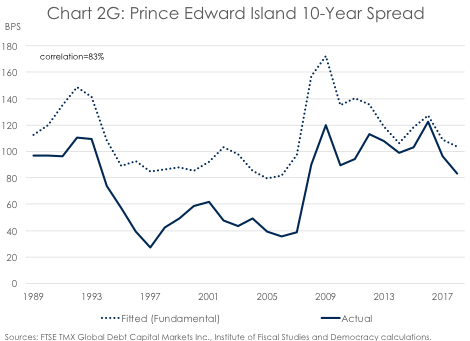

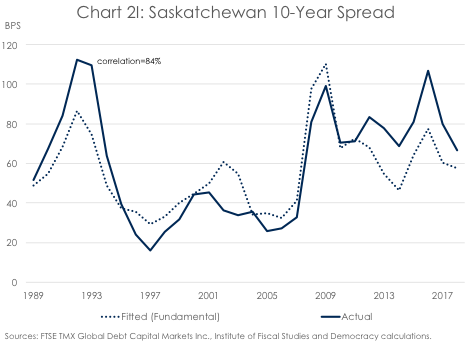

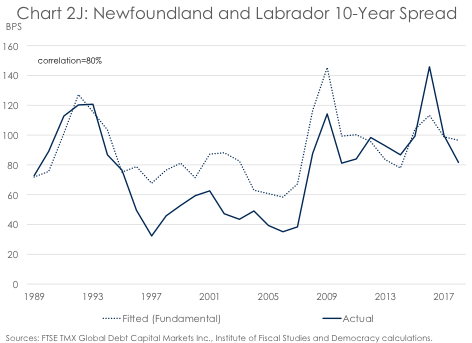

The charts below present for each province the model fitted values based on specification (1) in Table 1 above. Since we identified cointegration between the provincial yield differentials and the explanatory variables, the fitted values can be interpreted as fundamental values. In that context, we would expect provincial yields to converge towards their fundamental values in the long run. In general, yield spreads fluctuate around their long-term value both at the 10- and the 5-year levels. In some provinces, a decoupling of the 10-year yield differentials and their fundamentals happen after the 2008-09 recession (Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick, and Saskatchewan). Because spreads stay higher than their fundamentals suggest, a convergence could be expected in the future. However, a sustained gap between the actual and the fundamental yield differential is also observed in some cases. Notably, Quebec yields are lower than their fundamental throughout the sample while Ontario’s are higher. This could mean that the model does not capture all factors influencing risk premia. For instance, if actual yields embed not only current but expected deficits, debt, productivity, and employment levels, then a persistent gap could occur. Contrasting Ontario and Quebec, those gaps are also explained by different long-term dynamics in both provinces. For instance, Quebec has a higher net debt-to-GDP, lower employment-to-population ratio (until recently), and fewer outstanding amount of bonds relative to the federal government. Those differences increase the province’s relative yields. The gap between Ontario and Quebec’s fundamental 10-year yield spread is however on a downward trend, from 36 basis point in 1989 to 26 basis points estimated in 2018.